ourIslamOnline.net | home

II-PART

For the purposes of this discussion I will take one definition from a respected academic in this field. Jonathan Baron in his book "Thinking and Deciding" [Jonathan Baron, Thinking and Deciding, Cambridge University Press 1994] chooses to define being rational as

"the kind of thinking we would all want to do, if we were aware of our own best interests, in order to achieve our goals."

[Ibid. p3]

He then goes on to categorise thinking as being about decisions, beliefs or about the goals themselves.

Language and choices of definitions of its words can of course be highly subjective matter but I find this definition particularly inadequate because the choice of goals is entirely left to irrational and subjective choice and can easily be wrong. For example my goal could be to justify the equation 1=0 for which I would have to use very irrational arguments. If we build in the requirement that the goals are being, or have been, rationally set then we have a circular definition where any irrational goal would lead to completely irrational thinking which might, for example, be quite illogical. Then, this type of thinking would reinforce the irrational goal!

We cannot use this as a definition- at least until we have some clear refinement of it. Baron acknowledges this further on

"When I argue that certain kinds of thinking are "most rational" I mean that these help people fulfil their goals. Such arguments could be wrong. If so, some other kind of thinking is most rational."

[Ibid. p17]

If we are to understand from this that `people' means any person and therefore any goal then we still have the same problem. However, his arguments make sense because they appeal to the fulfilment of goals that people generally have. In other words if he uses the word people here to mean `people in general' then rational thinking is defined (at least in so far as goals are set) as being what people generally do.

This is a fairly major weakness in this attempt to define rationality in purely objective terms. You cannot describe rational thinking and forget that the criteria are themselves a matter of value judgement, such as the judgements made when setting goals. If one leaves the subjectivity of such value judgements in place then the objective approach fails.

Taking Baron's definition of rational from a different angle we could well ask what does it mean to be "aware of our own best interests"? This, in contrast to the above description, presupposes that there is such a thing as `best interests', which for all intents and purposes we can take to include the goals we set. This is closer to the position I shall take. There are such things as our own best interests, which include what our goals should be. We may not know perfectly what they are but we must assume that they are there, for without them any attempt to define rationality is self-defeating.

The goals we set, and therefore the very definition of rationality is governed by moral choices - by what our goals should be.

"Unlike many other fields of psychology, such as the study of perception where the emphasis is on "how it works", Much of the study of thinking is concerned with how we ought to think, or with comparing the way we usually think with some ideal."

[Ibid. p16]

The study of thinking is the area in which the `Is-Ought' problem is closest to being resolved. For to study thinking we must study what is `good thinking'. The Is-Ought problem can be stated as "It is impossible to infer, by any logical means, a normative statement from a descriptive statement." i.e. you cannot infer from any statement of the form "A is the case" the conclusion that "John ought to do X.” i.e. "Is" and "Ought to" . If we want to break out of this we must make value judgements. Using statements of value we can infer normative statements. For example, If I said "It is raining outside. Therefore you ought to take an umbrella." it would be an illogical inference. However, if I say "It is raining outside. It is good for you to avoid getting wet by taking an umbrella. Therefore you ought to take an umbrella." it is clear that the 3rd statement follows from the first two. The Is-Ought problem can therefore be seen as a matter of value judgements; how do we judge that something is good for someone - or for ourselves?

In these pages I am attempting to map out the solution to this problem by asserting that there are aspects of the way we think which we are morally responsible for - there is good thinking and there is bad thinking. There are ways of thinking that you ought not to indulge in and ways of thinking that you ought to adhere to. Once we have an 'ought to' statement accepted then it is possible to derive many other `ought to' statements and we have a consistent 'rational' framework for a system of moral guidance.

Returning to the description I brought up earlier, thinking broadly consists of two essential processes: searching and reflecting. Good thinking requires that we do enough searching and reflection about what we have found in order to guide our actions towards what is good for us. Good thinking also requires that we do not think so much that we don't act enough.

There are various ways in which we try to prioritise the searches we make and ways in which we choose to reflect or infer from those searches. How we prioritise these searches is of critical importance in determining whether the thinking is good or not.

In the Qur'an we find a very important verse through which we can draw the parallels firstly between the search element of thinking and `listening' and secondly between reflecting or inferring and `using our reason':

They will further say: "Had we but listened or used our reason we should not (now) be among the Companions of the Blazing Fire!"

Surah 67 Verse 10.

As I mentioned earlier, good thinking cannot be defined in terms of being successful at achieving goals that are in contradiction with reality. So we can start our description of good thinking by saying that one of the most important elements of good thinking is that it results in best knowledge of reality. Another way this could be put is that the overriding priority in the way we choose to search ought to be to seek the truth.

Related to this is intellectual honesty.

Standards and beliefs are useless unless a student has the goal of discovering the truth and making good decisions. Surely just about everyone has these goals to some extent, but the real issue is the strength of these goals relative to others. For example, good thinkers frequently find themselves reaching conclusions that they or their peers do not like; a strong commitment to "intellectual honesty" is required if standards of thinking are to be maintained.

[Jonathan Baron, Thinking and Deciding, pp131]

To say that you do not like the conclusions you reach reflects that you would have liked to reach a different conclusion - that is, your goals were at some level to reach a different conclusion. This dislike reflects a preference for previous beliefs about what would be concluded. This bias for previous beliefs is a very important issue in judging good or bad thinking and will be discussed in more detail later. To hold such biases is easier than having to remember new conclusions - it is a more lazy approach to thinking. To attempt to eliminate such biases is a more active approach to thinking. Lazy thinking is bad thinking so we must attempt to be active in considering new possibilities with an open mind.

Rejecting old beliefs can also have social costs, which I might call a political investment such as when someone makes a claim so that writing off the claim has a political cost. Someone could be overly concerned about what others think about them so that they may be tempted to be thought of as not making mistakes rather than someone who makes mistakes (though they learn from them). This is often a serious block to intellectual honesty. It is much easier to exist in an environment with like -minded people (i.e. people with the same beliefs) than to stand out for the conclusions you reach and attempt to convince others of them. To stand out in such a way requires strong intellectual honesty.

Before I go on to discuss Baron's formulation of this aspect of good thinking, I should like to mention a common attitude with regard to intellectual honesty that may result in atheism . Instead of realising that not liking the conclusions one reaches is from a healthy albeit wrong set of previous goals, they conclude that to have any goals in your thinking leads to intellectual dishonesty. This attitude gives us the equation of true intellectual honesty with the complete absence of goals. This is not true. Goals are always present in thinking and have driven the most brilliant thinking that human beings have ever achieved, it is only when those goals are wrong that they hinder good thinking. Some examples of this are inconsistencies and lack of symmetry in existing theories of physics which led physicists to seek a more symmetric and beautiful theory. The study of chemistry began by trying to find the various properties of materials so as to bring benefit to people. Indeed much research in science has been and is directed at the possible benefits new knowledge may bring.

The next thing to look at is what makes a good search?

Active open mindedness

Baron's criteria include allocating importance and searching in accordance with this, confidence appropriate to the amount & quality of thinking done, fairness to other possibilities than the one we initially favour. The search needs to be active rather than passive: we ought to be active in seeking out knowledge and we ought to be open minded in considering new possibilities, new goals etc.

To illustrate one aspect of the way we search, consider the nine dots problem.

Draw these dots onto paper. The task is to join all nine dots together without removing the pen from the paper using no more than 4 straight lines. (Drawing back over the same line counts as drawing another line.)

Give it a try. If after 5 minutes or so you still don't get it turn the page for a clue:

The clue is:

You can draw the lines outside of the box. To see the solution turn to the end of the book.

Justifying active open mindedness as part of rational or good thinking is done easily from the perspective of Islam and I will return to this further on. From an academic's point of view they will probably recognise the elements of active open mindedness as continually being taught indirectly within their (scientific) institutions. Quite simply within the realm of seeking verifiable knowledge of reality these principles are generally found to work. Whether they work for goals that aren't as noble as the seeking of knowledge is not so clear.

If you are not 'actively open minded' in your thinking your thinking may well become quite bad. Examples to the opposite of 'active open mindedness' include:

It is useful, now, to examine these in some more detail and how they relate to morals concerning thinking.

Biases in the search.

In the thinking processes where we are searching for evidence, we may be searching for clues and evidence by our actions or by searching our memories for something that may shed light on our investigations. There may be a number of biases in the way we think. We often search in a way that favours finding results that appeal to us already. A good example is in thinking about history. People sometimes want to demonstrate, for nationalist purposes, that their nation or people or culture is the best and so in searching for evidence, they look only for evidence and arguments that support their case and conveniently leave out searches that might yield evidence against their positions. To recognise this as bad thinking one has to recognise the goal of demonstrating that one nation is better than another (whatever better means). The search should really be concentrated in what is thought to bring the most decisive evidence, whether or not it is pleasing to the thinker. However this again depends on the goals of the thinker. Why should the thinker have intellectual honesty as the driving force? Where this becomes bad thinking is where intellectual honesty is compromised. It is of course a matter of degree and the more compromised the more serious this is (as part of the sin of disbelief)

Inactivity in the search

Inactivity in the search is really just another form of bias in our thinking. It results from trying to maintain intellectual honesty at the same time as keeping cherished beliefs, beliefs that are in possible danger if the search is too thorough. However, searching takes time and effort and you may have other priorities in life to spend your efforts on. There is a perception in this of diminishing returns, i.e. that the more you search the less significant the results will be. However, bad thinking in this respect will be in proportion to the degree of self-delusion about how whether the returns are diminishing or not. What these returns are and how well they fit into intellectual honesty is of course a value judgement decisive in the way we think and in what good thinking is.

Searching not in accordance to the importance of what the search is for

What is important is very much a value judgement; the importance will depend on what your goals are. If good thinking is to imply that you search in proportion to the importance of what the search is for, then it is first essential that the goals themselves are right; we must first search for our goals. What is important? I mean what is REALLY important? This is the most important question. The question can be asked as "what is good and what is bad?" or " What is the criterion for deciding good or bad?". If there is no absolute good and no absolute bad then what is important? Nothing. And if nothing is important then no thinking can be good and no thinking can be bad. (I will return to this theme in depth later) What is really important is whether anything is really important? Whether there is a single judge who determines what is good, useful, important and what is bad, damaging and useless, or just unimportant. This is the most important question: Does the judge exist, does God exist? - It is this question above all that deserves time and effort spent searching.

Confidence in the results, not appropriate to the amount and quality of thinking that has gone into reaching them.

As far as this relates specifically to future searches it manifests itself either as arrogance or as timidity. Arrogant people say, "I know - therefore I don't need to listen". Such an attitude prevents the search process before it even starts. Timid people say, "there's no point listening - I couldn't understand". Both these approaches make thinking bad, though arrogance is usually worse because timid people tend to follow arrogant people.

The next section goes on to discuss the part of thinking through which we reflect on the results of the searches. Of course the split is not clean between these two processes but it is helpful to use these splits in explaining good thinking.

Often the thing that comes to mind when we think about reasoning is logic. Logic has many systems generally stemming from the Greek philosopher Aristotle. We can talk of categorical or propositional or predicate logic. Here are some typical examples

All A's are B's and all B's are C's - Therefore all A's are C's

Some A are B. No B are C. - Therefore some A are not C.

If there is an F on the sheet of paper there is an L. If there is not an L on the paper there is a V. Therefore there is an F or there is a V.

Predicate logic combines these two and as we get deeper into the study of the logical use of language we come to semantics where we are no longer explaining the use of language but the meanings of words become restricted by limiting their use to meanings consistent formal definitions.

This type of reasoning, which I will call 'formal' logic, is only concerned with reaching conclusions with certainty from certain accepted statements. It is not nearly enough to describe the process of reflection because most evidence we get is not absolutely certain. To think logically in such a way that you follow the formal logical constructs mentioned here would also not be enough because it doesn't cover the search process. Good thinking is as much about finding the evidence in the first place as it is about deriving conclusions from it.

All of scientific knowledge is based on reasoning from imperfect knowledge; indeed none of what we know is 100% certain. We have to deal with probabilities and hypotheses. This gets close to a related issue, which is whether we can ever be confident that any statement we make about reality is absolutely true. We cannot. - Human knowledge is inherently imperfect and formal logic doesn't consider this.

Our 'beliefs' are generally formed by hypothesis testing and on the balance of probabilities. This can become subject to more rigorous tests than simple guidelines for good thinking in a search process. Sometimes a judgement on the balance of probabilities is clearly dependent on definite factual observations that frequency determines the probability or that the events are logically exchangeable. (e.g. tossing a coin and getting heads or getting tails). However, often judgement of the weight given to individual items of evidence may be a matter of personal opinion or choice. This latter situation is the case in most everyday situations; we justify our probability judgements based on the weight we give to certain pieces of evidence.

Whether this aspect of thinking is good or bad is dependent on a number of ways that our reasoning can go astray.

There are a number of ways that formal logic reasoning can go astray. These tend to have the same essential traits as the failings people have in their searches. These problems are usually to do with not thinking carefully or patiently enough.

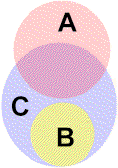

An example of this is given here: No A are B. All B are C. What is the relation between A and C? Many people say that no A are C. However this is wrong. More careful thought reveals the possibility that we can only say that 'some C are not A'. The easiest way I know to understand these syllogisms is to think of sets as represented by shapes:

It is now clearer what is being said. This is fully analogous to insufficient search. The difference here is that in principle there is a clear limit to the search in formal logic where you can be clearly convinced that you have deduced accurately all that can be deduced from the statements given.

However, bad forms of apparently formal logical reasoning can often come from having a difficulty in separating previously held convictions from the process of reasoning.

An example of this is trying to reach the logical conclusion here:

Some ruthless men deserve a violent death. Since one of the most ruthless men was Heydrich, the Nazi hangman:

. Heydrich, the Nazi hangman deserved a violent death

. Heydrich, the Nazi hangman may have deserved a violent death

. Heydrich, the Nazi hangman did not deserve a violent death

. Heydrich, the Nazi hangman might not have deserved a violent death

. None of the given conclusions seems to follow logically.

People tend to answer this in accordance with their beliefs and not to hold to the strict logical interpretations. The real answer to the above problem is #5.But most people choose 1.

Aristotle who developed this form of abstract formal logic also identified common logical fallacies that are still used in much of the current political talk and other areas. They all flow from mixing into the logic preconceived ideas of reality to give the appearance of a sound argument when in fact it isn't an argument at all. I will highlight only a few to identify the sort of thing that happens.

Ad hominem is where the argument is directed 'at the person' for example saying that the Nazis supported eugenics therefore eugenics is bad. This argument is flawed if we are to consider it strictly in terms of logic. Terrible people sometimes have good ideas. The flaw however here is only in the choice of mode of expression. It is not a logical argument but is put in those terms. For example, I might note that the Nazis also developed highways in Germany for the first time and developed the economy well in the early years, but does this mean I can use this to assert that building highways is bad? Of course not. The key to understand the difference is that the former argument makes the assumption that eugenics is already a bad thing. These types of argument use such built-in assumptions and put them in a way that the argument is loaded as in the question: "Have you stopped beating your wife?"

The 'Appeal to force' builds in the assumption that 'might makes right'. I lose count of the number of times that foreign policy is justified on grounds which if the names were changed to some other people then the argument would be completely rejected. Consider the labelling of Sudan as a terrorist-supporting nation allowing the imposition of sanctions. Though no evidence has been brought forward that Sudan has ever supported terrorism the charge sticks because it is made by the big and mighty US. But what of the US itself? Is it not in the US that the IRA freely and openly collected almost all of the funds it used in buying its weapons for terrorist acts? Should not the Europeans have put sanctions on the US for what they did? This is more than simply a logical fallacy it is a completely immoral deception and falls squarely inside the area of what can be called bad reasoning. The underlying perceptions of reality, which allow people to get away with such transparently false arguments, are really a problem. In the case just cited the assumption being forced on the audience amounts to `the US is always right'.

Another is the argument from ignorance. This is where a lack of evidence is used as proof of something. This forces the assumption that there has been an exhaustive search and there is no more evidence to find. This is a key example of the kind of arguments used sometimes by people trying to disprove evolution theory. But when the evidence is found their arguments fall apart. It is more accurate to consider what the actual search has yielded and to offer a qualified argument based on that.

Another is the 'appeal to multitude' e.g. " Most people smoke brand X. Therefore it is the best brand." Here the conclusion does not follow because most people might have bad taste. The assumption being forced here is that most people will always choose the best option. I remember being asked in school if I believed in God and if so why. I answered that I believed because so many others believed in God. It was the realisation of the fallacy in this argument that made me start to question my intellectual foundations more closely.

These types of arguments, as I mentioned earlier, depend upon accepting the statements (or forced assumptions) as unquestionably true and this is not usually the case. Usually, the premises of the way we reason are to varying degrees uncertain.

Almost all the real reasoning we do is based on imperfect knowledge. It is rare that we are dealing with situations in which we can have only given statements accepted as true as is the case in formal logic. Indeed even when trying to reason in purely formal logic people often bring in their imperfect knowledge of reality. We reach conclusions from our reasoning in a number of ways. Sometimes we have anecdotal evidence, sometimes we hear about surveys, sometimes we listen to people we trust. All these routes are used in everyday life in how we make decisions about what we believe and in what we choose to do. They also figure strongly in science, although science has a more earnest debate and can often rely on experimental evidence that is beyond dispute.

We weigh up the evidence in front of us and see where the balance of evidence lies. Sometimes it is a marginal issue. Sometimes there is a clear winner. In this process however there are a number of ways that we can combine the various bits of evidence in mistaken ways.

One way that people make mistakes can be called the `gamblers mistake' since many gamblers make it. It is to assume that the outcome of an event is dependent on previous events when it isn't. For example if the roulette wheel comes up black three times then the mistaken gambler thinks that there is a higher chance that it will come up red than black on the next spin (actually of course it remains a 50/50 chance). This invents a dependency and hence causal relationship between events where there is none. I suppose this might be termed a superstitious mentality. Other errors of this sort can be attributed to taking short cuts in working out the maths of combining probabilities. This can be seen another manifestation of insufficient search.

Another aspect of bad thinking people commonly make when weighing up the evidence is to put too much weight on evidence that confirms existing beliefs. Sometimes this is shown in the choice of tests made. Tests are made so as to provide evidence of existing beliefs where tests that might provide evidence of alternatives are not chosen. A good way of avoiding this mistake is to stay remote from the issue that is being considered. There may be good reasons why you don't want to consider the alternatives thoroughly and equally - change is difficult and has a cost. However, for the moral ideal of discovering what the truth is; what is going to be the best final result; what is the best solution for everyone, you need to ignore the changes that you must yourself make: The cost to you of changing your thinking and habits on a given matter is negligible by comparison to the total good for all by sticking to a pure detached search for truth.

When we try to think about morals we often find ourselves in difficulty. Morals are often passed down from generation to generation as traditions or maxims of lessons learnt. However, we face problems when we try to understand whether they are accurate or not. Before I tackle that, we must be clear on what a moral is. Morals describe how we as individuals or as groups should act in certain circumstances. A moral is moreover universal. What is right for someone to do in given circumstances is also right for someone else in similar circumstances. A moral can be stated in terms of 'If circumstances are X you should do Y.

However this explanation of what morals are leaves us with a significant problem. Can we logically derive any morals? Well many people argue we cannot. Formal logic doesn't allow drawing conclusions of the sort 'you should do Y' from any statement describing reality as described in terms of the categorisation that formal logic uses. This 'Is-Ought problem' was mentioned earlier when discussing definitions of rationality. However, we become able to talk sensibly and logically about moral statements only if we accept the reality of value statements.

The remainder of this section is concentrated on trying to bridge the is-ought problem by asserting the real value of certain ways of thinking such as 'Logical thinking is good'. This 'real value' implies that there is some true value to our actions; something universal to how we behave that makes our actions worthwhile. It is this that makes an action morally virtuous.

These assertions have their limits, indeed they could be rejected out of hand if someone takes a stand that asserts that such values aren't real. Such a person has a point. We did not reach statements such as 'Logical thinking is good' from within the framework of formal logical reasoning. It was in fact an assertion from the outset. It is made because it is probably going to be accepted by most people with sound minds. However, I will now add to that general statement the assertion that value judgements are real and important. Instead of thinking in terms of abstract categories of things, as formal logic requires, we should become comfortable with values associated with things. Instead of saying 'logical thinking is good', we can say that 'good thinking includes using formal logical reasoning'.

How this can lead us to a more general set of morals should become clear in the following pages.

Moral relativism is a recent development, which asserts that the only reality to values is the reality to the holder of those values. This is however a complete misuse of the word `moral', since (as is mentioned above) a moral has a universal implication. If I believe a moral then I believe that it is true for all people who are in similar circumstances. I may not agree with others on this or that moral but the disagreement must be put down to imperfect knowledge. It is certainly not the same as saying that both our judgements are right. In moral relativism, values are asserted to be completely subjective - they have no objective reality other than their manifestation in the choices people make.

If we accept the ideas of moral relativism we must admit frankly that there is no such thing as good thinking - I might like deceiving myself and paradoxical illogical thinking. Would it then be the morally right thing for me to do?!

How can I debate and discuss any matter with someone who believes and talks nonsense half the time and feels there is nothing wrong in doing so?

If values aren't real then there are no morals and there is no good thinking, there is no particular right choice of sources of knowledge and there is no real knowledge only assertion. Of course this argument could be rejected but to do so is nonsense.

There is a very important consequence of dealing with real values. If what you're doing has real value then your life has (potentially at least) real value and then so does humanity and existence in general. That which is good fulfils the purpose of creation and that which is bad opposes it. This means that what you do in life matters; how you live matters. You can either live in such a way that your life contributes in some way to the benefit of your life, humanity, life in general, existence, or you don't.

If there were no purpose to existence then everything you do would be utterly worthless and futile. At the end of it all, whatever you did with your life, whatever you became is completely irrelevant; nothing you did was worthwhile.

You may as well have never existed.

If on the other hand there is purpose to existence then what you do and what you are is important. You can make a real difference. There needs to be a judgement of the fulfilment of this purpose, of the real value of your role in existence. That judgement must be by God - no one else is qualified.

It is worthwhile being alive.

We have now reached the topic of belief in God. Many people in the West have already got well-developed concepts of what God is - though this is changing with people in Europe, where religion itself is almost taboo as a serious subject. The arguments that have been presented so far are really concerning God as the ultimate source of all real value. Anything that is really good flows from God's compassion and mercy: in Arabic one would say God is Ar-Rahman.

Disbelief in God therefore has the primary implication of disbelief in morals and values. If you disbelieve in God in the sense of Ar-Rahman then you assert that none of your deeds can have real value.

The sin of disbelief in God then is a profoundly important one since it is profoundly tied up with sin in general. The subject of the concept of sin in general will be dealt with later, but for now let us consider the evidence which is relevant for this belief. The sin of disbelief in a particular revelation will also be considered later.

The strength of the argument so far lies in appealing to what makes sense to human beings. Human beings need to value and be valued and it makes sense to us that those values are real.. There is nothing weak in making such an appeal; indeed the appeal to good thinking is similarly an appeal to part of human nature. An appeal for good thinking includes an appeal for consistency with what is already accepted and for the acceptance of clear evidence. Muslims commonly know Islam as the natural way of life (din ul-fitra) because it fits this human nature perfectly. Another aspect of this argument flows from the in-built sense of justice in human nature, which requires that there are right and wrong deeds and that we are accountable for them, though to discuss this now in depth would take us off the track.

The nature of evidence which convinces us of the existence of real value is the type of evidence which brings about in us a sense of awe; of appreciation; a recognition of beauty and the conviction that all this cannot be here for no purpose; it cannot be just an accident of no consequence; it cannot ultimately be worthless like an idle game.

The design argument is often presented in a fairly confused way. It often seems little more than a declaration of being closed minded :" I cannot understand how natural selection could have made such wonderful creatures!" How could this have come about through chance?"

Once an explanation is given, the person putting forward the design argument generally fails to accept the explanation although many people are willing to concede that it offers at least a plausible explanation if not a quite powerful explanation of how creatures came into existence.

To make things clear: There is nothing in the Qur'an which contradicts the explanations of the origins of life and its evolution that are found in contemporary evolutionary theory. In fact there are some statements that confirm parts of that theory such as

…. - and [that] we made from water every living thing? Will they not then [begin to] believe?

Surah 21, Verse 30:

When I look at the wonderful forms of life around, I appreciate their beauty and their design. Evolution is reasonable and based on some solid evidence. It is, however, more difficult to prove because it is hard to contrive experiments that take place on a reasonable time scale.

The design evident in life is even more impressive when we can start to understand how it happens. We can then appreciate the design process as well. If we appreciate something we value it. As we study the life around us we see the design process of natural selection at work making life forms embody survival lessons from their environments more and more, we find it more and more impressive & more and more beautiful. We then exclaim that all this could not have happened for it simply to end in nothing; that existence should be more than a cruel joke or an idle game signifying nothing.

This point is at the heart of the design argument. A design is such not only because it has a designer but because that designer has some good purpose for his design.

Life's purpose is to learn about reality. The lessons are embodied largely in its genetics.

Man's purpose is to learn about reality, think about it, appreciate it & hence come to know and adore its ultimate source and destiny - i.e. to worship and serve Allah.

An important part of good thinking is to understand the point at which something requires no further explanation. Most people are aware of the series of questions that a child may ask as explanations of the world are given to him or her. The child continually asks "Why?" no matter what answer is given. Usually the parent runs out of answers at some point and says something like "It just is!" or "Because I say so!". These are not good answers. They are, in the first case, unreasonable and in the second case a bold-faced lie. It is much more accurate and reasonable to say "I don't know" once you reach the point at which you have no more answers.

We should always expect that answers exist to the question 'Why?' (or 'How?') - it is an essential part of our reasoning nature. If at any stage in the explanation I answered by saying 'It just is.' I would rightly be accused of being unreasonable. No one could reason with me because I would be stating that there is no reason for the explanation I have just given. To take such a position is to assert that your explanation is the truth. This, besides being unreasonable, is very arrogant. It doesn't recognise the limitations of human knowledge as mentioned in the section on the basis of knowledge. In Islam the first characteristic of the faithful (muttaqin) is belief in the unseen (al-ghaib). This stresses that the first characteristic of a Muslim is acknowledgement that his knowledge is in principle limited and that part of reality is always unknown because it is unseen.

Asking 'why?' can be split into 2 meanings. The first is to mean 'How?'. This question digs ever deeper into understanding the causes and descriptions of reality. The second meaning is 'So What?!' and boils down to asking what is the value of something. I have partially dealt with this element earlier. The ultimate answer to the 'So What?!' type of question is the purpose of all existence. It is why we exist.

In searching for ever better explanations of how existence behaves we always expect a deeper level of description. Whatever answer I give to describe some aspect of reality, it is always rational to ask why in the sense of how. For example, Why is this piece of paper white? - Because the molecules in it scatter the light. Why? Because the chemicals in the paper reflect all wavelengths of light so that on average all wavelengths combine to make the reflected light white. Why do the molecules reflect light?.... and on and on and on. There are still many, many unanswered questions in science.

The point at which our reasoning comes to a stop is where our knowledge ends. Asking for explanations beyond that must yield the answer "I don't know". However, you may still theorise and ask 'what if ...' type questions. The point at which this questioning could end would be the point at which the concepts are beyond human understanding; when the explanation lies outside of human experience and therefore is in essence inexpressible in human language. This is the thing of which we cannot rationally ask 'how?'; it is that which, by its nature, we have to say we can't know.

This point in our explanations is the ultimate explanation of reality. It is the ultimate metaphysical reality.

You may have other names for it but it is the same thing - the truth - the beginning and end of everything - God - Jehovah- Allah.

So far we have only dealt with the sin of disbelief in God and with the general framework of the basis of knowledge in terms of good and bad thinking. The sin of disbelief in God is essentially the product of rejecting the effort to do what is morally right. This applies to general actions and in particular to exercising good thinking as it would inevitably lead to belief in God as the ultimate explanation of reality in both the senses of the question "Why?" i.e. "So What?" and "How?".

What makes good thinking is at the core a question of sincerity and when one rejects good thinking one is essentially undergoing self-deception of one form or another. It is not necessary to be intelligent to have good thinking - though good thinking may well lead to greater intelligence. What matters is sincerity; wanting to do what is morally right. Someone who practices good thinking is essentially someone with a clear conscience. Insincerity and self-deception are core to the concept in Islam of the disbeliever. The word used for disbeliever in Islam is "kafir" and has the literal meaning of someone who covers up. I could go into many quotes from the Qur'an of the nature of kafir but I'll leave that to the reader to discover for themselves. What I will quote here is the essentials of belief which apply to all people:

...any who believe in Allah and the Last Day, and work righteousness, shall have their reward with their Lord; on them shall be no fear, nor shall they grieve.

Surah 2 Verse 62

This brings in the subject of the last day or judgement day. The need for judgement day can easily be understood once moral teachings are recognised as having real meaning. Moral laws are like physical laws. If I am in a state of self-deception as to the laws of physics I might decide to punch my hand into a concrete wall. It would hurt me a lot but that is the natural law. It is the same way with morals. If I refuse to acknowledge that which is evident to me and I do something to spite it, I am only going to cause harm to myself in the long run. If I deliberately do wrong it is no different from me punching my fist into the concrete I should expect it to hurt and I have no excuse. The difference with morals is that the consequences are sometimes well into the future whereas punching concrete has an immediate consequence.

However, all this only gets us so far. Morals relate to how we should act over such issues as the use of drugs, sexual morals, use of violence etc and this concerns much more that the general principles we have been discussing so far. Morals can be learned to some degree through life's experiences, cultural traditions can get passed on through the generations and sciences can come to some sort of conclusions. However, morals are often considered to be different from descriptions of the physical reality around us and indeed they are. This is the `Is / Ought' problem again. In the earlier pages I have in a way partially bridged this divide by tackling the very categorisation: we only have 'Is statements' because we keep to a foundation of good thinking which results in our knowledge. That said, we still don't have a firm basis for deriving morals; we have really only asserted the integral and essential nature of moral intent in the way we observe and think about reality in general. How can we approach, for example, the question of the morality of drinking alcohol? To judge an act to be morally right or wrong, we need to know the ultimate consequences of its effects. This we are in principle not able to do, because such knowledge is beyond our ability to know. We can only know a few of the effects. Morals also are not subject to experimentation as are purely non-living phenomena. We cannot morally justify forcing people to behave in certain ways to see the effects. Indeed any forced behaviour cannot be moral because it is not freely chosen. The only real source of legitimate knowledge on this subject is history. History tells us that no culture has ever maintained morality over time without having a strong religious underpinning. This is because the only source of suitably qualified moral teachings is the ultimate cause and explanation of reality, who is therefore all-knowing and the one who knows the ultimate outcomes - Allah.

From this we see that revelation has been the source of moral guidance throughout history. The question that is critical though is to distinguish between genuine revelation and fake. How are we to know what is true revelation from Allah? To answer this I shall return to the concepts described before in the sin of disbelief. To really resolve the `Is / Ought' problem we use the principles of good thinking to analyse the evidence that some scripture claiming to be revelation actually is revelation. First we must consider what kind of evidence would demonstrate the truth of a revelation.

The nature of signs that demonstrate a source of revelation from God to humanity have changed over time, but have all been to convince people in accordance to the science of their day. In the time of Moses the science of the day was the trickery of sorcery. To know how to impress people with such things was the highest form of knowledge. Moses was given many miracles but among them were that his staff turned into a snake and that his hand shone bright white. In the time of Jesus the miracles he brought were similarly in tune with the best science of the day - he healed people in miraculous ways. These things were all convincing to the people in the sciences of their day. If you had been healed by Jesus or seen the staff turned into a snake you would have had no reasonable excuse to reject the revelation brought by these people. Another thing has always been critical in sciences thought out history, and that is the prediction of the future which is the basis of the usefulness of all science, indeed this is the common meaning of the word prophet in English.

So where is the evidence of revelation today? What would be the nature of such evidence today, which would be convincing to the sciences around now? For that matter what would be convincing to future scientists?

The nature of the evidence is that of the scripture itself - its meanings its style, its knowledge. It claims to be a text that cannot be explained away: - for many reasons the evidence points to the convincing conclusion that it was not composed by any one person or by any group of people. This is known as the ijaz of the Qur'an.

The Qur'an had a huge impact on the world. It transformed the Arabs from a bunch of warring tribes into leaders of the most powerful empire that had ever existed. It was the reason why the classical Arabic language has been preserved to an extent incomparable to any other classical language. It was a completely new style of literature that had no precedent and has had no text approach its unique poetic prose with powerful meanings. Although it is sometimes hard to put the meanings into English I will attempt to bring some of this across in a discussion on the opening surah of the Qur'an which is a mere seven verses but which is packed with profound meaning. I will also introduce a couple of examples of remarkable subtlety.

To directly appreciate the signs of the Qur'an it is necessary to know Arabic, because only then can you really see the full range of meanings of the words employed. You can then apply your knowledge of reality to those meanings and appreciate more fully the accuracy and eloquence of the text. To the Arabs of the time its power as a text was profound and a few verses were able to transform the lives of people. This occasionally was partly the result of the context and timing of the revelation which gave a clear meaning to the verses sometimes giving accurate predictions of otherwise unexpected events, but often the listener recognised the text as speaking directly to them and from a position of knowing them intimately as only God could have.

It is sometimes said that you cannot simply read the Qur'an, rather you have to answer it - it challenges you directly from a position of completely unquestionable authority. You must answer. Many people who would like to consider themselves balanced and fair minded are unnerved by the text. They simply don't like to be challenged. It is hard to really read it and earnestly seek to understand the meanings without reflecting on what it means for you.

These things await the earnest seeker of truth when they read the Qur'an, however for now, I would like to consider the evidence which I can easily relate to someone who doesn't speak Arabic. This must inevitably depend on my knowledge of Arabic, which is somewhat limited. I have, however, studied some Arabic in the key areas, which I cover in the following pages. The principal evidence of the Qur'an which I aim to present is of remarkably accurate descriptions of phenomena found in the Qur'an which have been discovered only recently many centuries after the Qur'an was written as well as the beginnings of some discoveries in the numerical structures in the Qur'an which have become available since the complete concordance of the Qur'an was first compiled in the middle of this century.

These are part of the perfection of the Qur'an is evidence of the perfection of its author. My knowledge is imperfect and any errors I may make in this are mine alone. The Qur'an makes the powerful and important challenge that if the Qur'an were by other than Allah then there would be much error in it. Indeed if you look at any text contemporary with the Qur'an you will find in it many things which when looking back with hindsight we recognise as errors. It is indeed remarkable that none of these have found their way into the Qur'an. To prove there is no error in the Qur'an would require me to go through the whole Qur'an explaining every verse - even then this doesn't prove it against future discoveries. All I attempt to do here is highlight the remarkably accurate statements and impressive structure in the Qur'an and refute some things that could be mistaken for errors. I leave the rest to you.

When I first thought seriously about becoming a Muslim I made a point of reading the whole Qur'an to see if there was anything which I would find intellectually unacceptable. I found nothing of the sort. On the contrary, I found several things that strongly confirmed my tentative newly forming belief.

The sin of disbelief as far as revelation is concerned is closely related to that of disbelief in God. However, there is an important distinction: Disbelief in God is the equivalent of bad thinking. Belief in God is essential for good thinking: it provides the ultimate rationalisation which makes the believer's perspective on reality a 'rational' one and the ultimate goal to what makes thinking really good. Disbelief in revelation, on the other hand is the consequence of bad thinking when encountering revelation. It is possible to believe in God and not accept the Qur'an as genuine revelation. If someone disbelieves in the revelation of the Qur'an then it is not necessarily a sin. It will depend on how good their thinking is, given the knowledge that has reached them. Good thinking implies that the search made was a reasonable one. It is no excuse not to gain knowledge that may be vital for you when it is at your fingertips or even if you need to put some significant effort in. A reasonable search will of course correspond to your estimations of success in the search. For example there is no reason to expect to find banana trees growing at the North Pole. If your expectations are genuinely very low of finding something important, and your perception of the risks of not finding something is not high then you are not guilty for not putting much effort into the search. Your estimations are based on your knowledge. Allah knows what you know to be a reasonable effort. You will only be judged as sinful in your not accepting some particular piece of revelation if your thinking was bad; if you had some lack of sincerity in seeking the truth as to the claims of the Qur'an.

"Ad-din an-nasiha" - the religion (Islam) is sincerity

Saying of Prophet Muhammad (peace and blessings be upon him)

So far we have concentrated on the sin of disbelief in Islam. To wrap up that discussion it is necessary to put it into context within the general concept of sin in Islam. A sin is an act in contrast to the will of Allah. We can act following His will, this is the meaning of the word Islam, or we can fail to pay attention to His will or we can deliberately act against His will. Islam is submission to the will of Allah. The purpose of our existence as Human beings is to worship and serve Allah - to do His will.

This is made clear in the Qur'an:

"I have only created Jinns and men, that they may serve Me."

Surah 51 Verse 56

Yusuf Ali Translation:

"I created the jinn and humankind only that they might worship Me." Pickthall Translation:

The most important names of Allah are ones expressing His compassion towards creation - Ar-Rahmaan and Ar-Raheem. These mean the most full of compassion and mercy (Ar-Rahmaan) and the most giving in that compassion and mercy (Ar-Raheem). The foundation of worship / service to Allah is to become humbly grateful for the great gifts we already have from Allah and as a result to seek to please Allah through serving Him. This happens through gaining knowledge of creation and recognition of the revelation sent by Allah to Mankind and learning to value and appreciate it. We then serve Allah by building in and on that creation to add ever more real value to it.

To serve Allah our intentions must reflect His intentions; our wills must be consciously submitted to His will. The basic principle for us then is to reflect Allah's 'rahma' by showing compassion and mercy towards Allah's creation in the hope, and with the assurance, that Allah will show compassion and mercy towards us.

One of Allah's greatest gifts is the gift of moral guidance through revelation. If we follow it, it brings the greatest benefits in this life and the next. It is in trying to do this that our intentions are purified and it is by our intentions that we are judged.

A fundamental precept of Islam is that Human nature is essentially good. There are many elements to Human nature and each one has the potential to bring benefits.

In general we can say that a sin is committed when someone causes harm to themselves or to others or to any part of creation. The guilt depends on the intention of the sinner. In its most extreme form someone does deliberately harmful and destructive acts rejecting any appeals to do what is for their own benefit never mind what is beneficial for others. They may claim that it makes no difference anyway since existence is pointless and therefore have no gratitude for the benefits they have in life.

The contrast to this is someone who tries to improve himself, others and all of creation. They believe in God and are always grateful to Him for all they have in life. Their works to improve creation flow from their will to please God.

Human beings have the capacity to sin largely as a result of having the capacity to plan. When someone plans their efforts, they need to be able to suppress their natural desires for a time. This is quite different from animals that live from moment to moment obeying their perceptions of the present and their instinctive drives. This is indeed a dramatic difference. Human beings are able to look to the future - conceptualise it and form an intention to act. This conscious intention can override even the most powerful of our instincts. Through it we have capacity to cause ourselves harm in the short term in order to realise the greater good in the long term. As an inevitable part of this we gain the potential to cause ourselves harm, i.e. the potential to sin.

We cannot see clearly into the future. What we do instead is to believe in some future circumstances and direct our actions accordingly. Taking planning to its logical limits we would try to do what is for the good over all time and certainly for our entire life (in this world and the next). This is the core of trying to do what is morally right. It is trying to do what is for the ultimate good. It is trying to do what Allah wills.

Islam's view of Christianity is that it started off as a religion based in Jewish tradition but accepting Jesus as a prophet and teacher. In time these teachings got replaced by corrupted teachings that Islam rejects: Jesus was not God incarnate and he was not God's begotten son. Islam's view of other religions generally is based on them having received, at some point, prophets which taught the pure monotheism of Islam along with fundamental concepts of the religion such as the nature of sin and forgiveness. These religious teachings have become forgotten and corrupted over time and so God renews His revelation again and again until in the final revelation the message is preserved intact. This is taken to be the revelation given to Muhammad primarily in the form of the Qur'an.

There is much more to Islam's view of Christianity than I shall detail here, however my concern is only to identify the sin of disbelief in Christianity and to compare and contrast this with Islam.

It is quite hard to speak of Christian beliefs without being inaccurate because there is a large variety of sects. What I am referring to here is the form(s) of Christianity that I am most familiar with: namely mainstream Catholic and Protestant Christianity.

In Christianity the disbelief in God and disbelief in revelation are also key sins. They are however somewhat secondary to disbelief in the resurrection of Christ. As a Muslim, I believe Jesus to be a prophet and a great teacher who brought great evidence in the form of miracles. I try to follow what he taught in so far as I trust the sources through which I find out what he taught. This, however, does not make me a Christian. To be a Christian I have to believe that Jesus died on the cross to save Mankind from their sins; that Jesus was God incarnated as a man and that God is Trinity rather than Unity.

It is the acceptance of these doctrinal points that makes one a Christian. If you don't accept these you are not a Christian. (This at least is the definition of Christian that I shall be using.)

Historically many people called themselves Christians who did not accept these doctrinal points and today many people consider themselves Christians but have never really thought about these points. How these doctrinal points came to be part of mainstream Christianity is not my concern here. What matters is that they are incompatible with the sin of disbelief as it has been set out in the previous pages.

The aspect of the sin of disbelief in God connected to the purposiveness of existence (i.e. if existence is purposeless then everything you do is futile and worthless) is a line of argument that still applies with Christianity because in broad terms Christians consider themselves monotheists and believe that there is only one judge. Some Christians, however, may think of God as essentially two judges or maybe three with Jesus playing the role of lawyer who needs to be persuaded of your case before he appeals to God on your behalf. In Catholicism the graves and images of Saints were and are worshipped and asked for favours etc., These things pollute otherwise pure intentions by appealing to different judges, who in principle may judge by different criteria. This damages or destroys the idea of universal morality and absolute rights and wrongs. If there are many criteria there are many purposes of the universe and you choose which purpose to work towards. No deed of someone who believes in many judges can be said to be good or bad in absolute terms.

This is strongly connected to the concept of salvation through Jesus dying on the cross. By this act all the sins of Christians are supposed to be forgiven. This great act must have changed something about the way to salvation, i.e. that before the act people had a certain route to salvation and that after the act the route to salvation is profoundly different. However, if God fundamentally changes the way he judges people in different times from being harsh to being easier, then this can hardly be justice! Is this a change in God's justice or is it rather two judges: God the father and God the Son. On the other hand, if there is no fundamental change in the route to salvation, then why all the fuss? -it doesn't really matter whether Jesus died on the cross or not; there has always been one justice and one judge.

The aspect of the sin of disbelief in God being the ultimate explanation of existence is a line of argument that might apply to Christians but generally doesn't. The problems again lie in the paradoxes of the Trinity.

Essentially both religions assert that they believe in a God whose nature is beyond the human mind to comprehend fully. There is however a significant difference in the perspectives of why God cannot be fully comprehended by man. In the Islamic perspective the metaphysical existence believed in which includes as its core God is called 'al-ghaib' which basically means 'the unseen'. This specifically refers to observation rather than the sense of "I don't see that" meaning, "I don't understand that". For example it could be said that the sun, when it is not visible to us at night, is part of 'al-ghaib'. Metaphysics in Islam is unknown essentially because of the limitations in our sense perception. In contrast to this Metaphysics in Christianity is unknown largely because our natural reason cannot understand it. God is 'above' logic.

At the heart of Christian doctrine is a profound mystery of paradoxes (e.g. everything belongs to God, He has complete power over everything. So in what sense can God sacrifice something? What does He give up? How can God be all knowing and at the same time not know what is going to happen? How can God become a man? See also "God made flesh?")

The effect of this is that the sin of disbelief in Christianity can't use a deliberate breakage of basic logical reasoning as a foundational element in the sin of disbelief. Christians don't merely 'not always expect better explanations' to their questions about reality, they also have no problems with explanations that are logically self -contradictory or paradoxes.

In conclusion the sin of disbelief in Christianity, because of its doctrinal beliefs, is far from the description set out above. Believing Christians can be very bad thinkers and people well informed about Christianity and extremely good thinkers may never become Christians. To illustrate the point I'll relate an incident that I heard about recently:

A woman brought up as a Christian accepted Islam and after some time decided to tell her mother of her decision. Her Christian mother asked why she had become a Muslim and she replied "Islam makes more sense" to which her astonished mother replied:

"But religion is not supposed to make sense!"